There I was. Neck-deep in npm packages, third-party components, Vercel deployment settings, and everyone's favorite JavaScript library, when I got the bright idea to update all of my project's dependencies after many months.

Boom. Like I'd Thanos-snapped my repository. Nothing worked as expected.

Now sure, we've all been there. But while I was preparing myself for the slog of getting my project into a working state again, I found myself particularly annoyed, and started reflecting on a bit of advice that I'd read months prior. I decided something needed to change, and that the web (arguably most software) should be simple.

Node.js Broke Me

It wasn't the first time this thought had occurred to me. Before I'd ever heard of Next.js, I'd read articles like The Bloated State of Web Development and Just Fucking Use HTML. I knew it took a lot of moving parts to get web apps running, but I just accepted that this was how web development worked. Meanwhile, even routine backups started becoming an issue: if I wanted my local repositories on my NAS, I'd either have to upload every node_modules/ folder with them, or create my own sync rules for each folder. I spent a weekend on this problem alone, but again, this was just how it was.

“Besides, frameworks make things simple,” I thought. “The templates and component libraries are just so convenient.” And so, I carried on watching videos and reading about Vercel, deploying Next.js projects. After all, this was how “modern” websites were created.

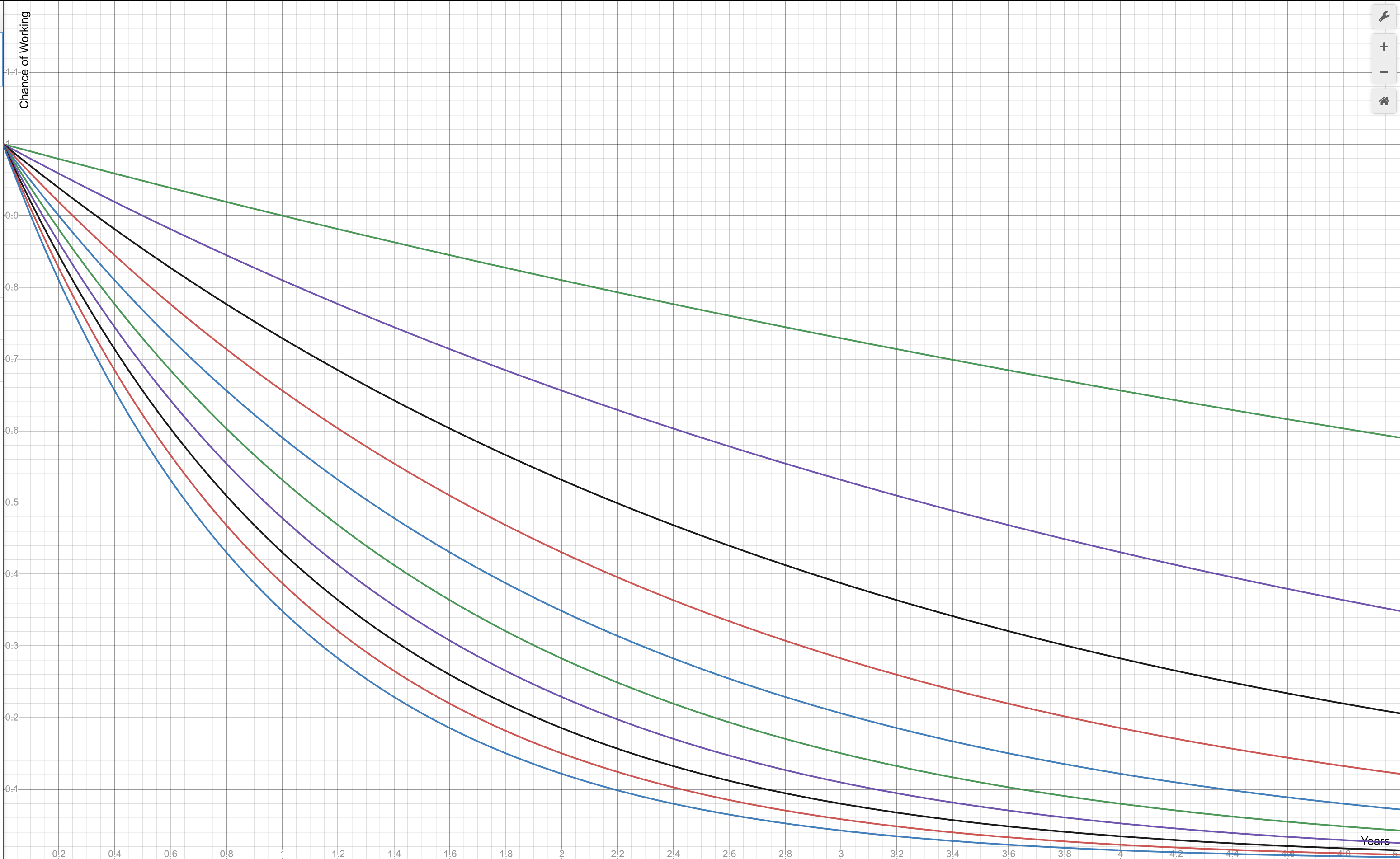

Recently, I read a thread from Casey Muratori about “dependency culture” in software development, and what it means in the long-term for projects when you add more dependencies to them. In it, he describes how “the probability that (a project) build remains working after x years is p^xn, where n is the number of tools used in the build.”

If we assume a 90% chance that the tools used in a project still work after one year (which is very generous in today's world, as Casey points out), then with just 3 tools there is very little chance that things will work as expected after five years.

While Next.js had obviously appealed to me at some point, I started to evaluate if it was even necessary for me. Even with hosting, did I really need to use Vercel, the creators of Next.js, in order to host my website? I found myself on edge due to a slew of questionable billing practices that had started plaguing popular web applications hosted on their platform. While it's true I'd (likely) never encounter these issues myself, it didn't sit well with me.

So I took a leap from the warm embrace of a managed platform, said my tender goodbyes to my frameworks, and decided to try something I'd never attempted before: rebuilding my website so it's served from a single file. More specifically, a compiled Go binary running on AWS Lambda.

Simplifying

Just by looking at these two project directories side-by-side, the difference is insane. My old Next.js project was super dense. There are many files, folders, and lots of components being used throughout various pages. And that's before adding any serious functionality or getting too heavy into the design.

My Go project wound up simpler than expected, after a couple iterations. This is the second time I've rebuilt it, and I'm pretty happy with the progress I've made! Just for comparison, I've gone from 62 files down to 6, not including my blog posts. Nearly all of the functionality lives in one file, while the other five serve as HTML templates used by the standard library's html/template package. This package turned out to be a huge saving grace, which I will touch on in a second, but it simply uses those templates to generate injection-safe HTML.

You can imagine the amount of dependency bloat that vanished. With my previous project, I was dragging along that massive node_modules directory that had packages for everything: fonts, components, framework features I wasn't using. Just looking at my package-lock gave me so much anxiety that I decided to act like it wasn't there.

In contrast, my Go project is lightweight and uses two dependencies. No more pausing auto-backups so I can add rules to a directory before my NAS decides to try devouring the sun.

My First (and second) Go

On my first Go at this (last pun, I promise), I made some hasty design choices. My first iteration relied on four dependencies: I decided to try creating my pages with Templ which offers type-safe HTML templates, and Tailwind for styles. I had heard about gohugoio/hugo, but after reviewing the dependency list, I felt like I was getting drawn back into the exact thing I was trying to get away from (ironic, in hindsight).

Something Google served up to me, which I thought was a great idea at the time, was gorilla/mux for defining my routes. This adds some routing features to the standard net/http package like support for path variables and method routing. The documentation was pretty solid for everything, and I got a few simple pages rendering without many problems. As I started fiddling around with Templ's AWS hosting guide and integrating markdown blogging with the help of yuin/goldmark, I was hit again.

“Do I need compile-time checks and type-safety right now? Components?” This feels familiar.

“Wait, if I'm serving static HTML, do I need something more feature-rich than net/http to create my routes?”

Suddenly, it was back to the drawing board, and I started working on a second iteration. After a few days of reading around, breaking things, and finding out, the project had become much more succinct. Templ was replaced by the standard library's html/template package, gorilla/mux was removed entirely, and I abandoned Tailwind. The latter will be dearly missed o7

After some simple tweaks and better templates, I managed to build a viable website + Markdown blog with two dependencies. Apart from the standard library, these were: algnhsa for adapting the standard net/http handlers to run on AWS Lambda, and yuin/goldmark for parsing my Markdown blog posts into static HTML.

That's it. A bit of HTML, CSS, and Go. The project compiles into a single binary, and instead of relying on Vercel for hosting, it gets uploaded to a Lambda function. With the AWS CLI, that part was straightforward on its own.

But what about my domain? This is where I had to start digging into AWS.

Why Not Self-Host?

While I love the idea, self-hosting was out of the question for me. After all, what good is a website if the mildest storm could knock it out? In my case, I reached for the next best thing: AWS. The free tier features were good enough for my purposes, and honestly the hardest part was figuring out how to navigate their portal.

I was wary of getting too deep in the trenches, and I am thankful that there were many online resources to help along the way. Thanks to a few articles and videos from YouTubers such as Micah Walter, codeHeim, and AWS with Jaymit, I was able to grok most of what I needed to know to get everything up and running.

If I wanted to use my domain for this Lambda function I'd created, I have to start at Route 53, which handles DNS. After pointing my domain's nameservers to the ones AWS provides, and requesting a public certificate, this whole setup didn't take long to propagate. This lets my domain point to a CloudFront distribution, which is AWS's content delivery network (CDN) that handles HTTPS, caching, and routing traffic.

From my domain, CloudFront forwards the request to AWS Lambda, where my Go binary lives. After spinning up a container, the binary is executed, renders the pages, and sends back a raw HTML response. Presto, everything's automagically delivered to the user's browser.

There's no Node process watching for changes, no runtime React stuff booting up, and no Vercel deployment pipeline I need to watch like a hawk. It's just a binary, waiting to be invoked. In the future, I will certainly be looking to fully self-host, but for now I also kind of wanted some experience with the AWS environment.

Notes

I'm not saying everyone should rewrite their website in Go or worry about hosting and configuration. For me, I just wanted to build something simple and challenge my perception of modern web development. I stripped away the layers and made something that just works. It deploys with one line, I can run a cron job to detect changes in the project directory, my blog lives in my Obsidian vault, and I'm pretty happy. There's plenty I could be doing, a few features left to work on, but overall I'd say it's been a successful project so far.

“Simple pleasures are the last refuge of the complex.”

- Oscar Wilde